Text from a short article published in Lobby Magazine Issue No.2 "Clairvoyance"

Rio de Janeiro, 2016. In this age of digital social communication networks, internet-enabled cameras have given new freedom to the everyday user to autonomously record and transmit their visual experience of cities and architecture. At the same time, the built fabric of cities is also changing quickly, but is being driven largely by corporate greed and political scuffling. To set the scene, on one side of the camera lens, there is media revolution, on the other side, disconnect between city inhabitants and city planning. Acting as a secondary technological mediator in the user’s experience of the city, Ghost Landscapes is a proposal for an optical interference installation which would form a large-scale subversive architectural protest through the hacking of photographs taken in the 2016 Rio Olympic Park.

A starting point for the project was to consider how cities and architecture perform to this new media revolution, both in celebration and protest: on the one hand, large scale, ‘spectacular’ constructs, such as the Olympic Games or the World Cup have a specific intention to be consumed in this way: stadiums, monuments and plazas, emblazed with sponsors’ logos can be pasted over existing fabrics, forming a seamless microcosm of the city ‘fit for publicity’. On the other hand, Rio’s preparation for the events in 2014 and 2016 have been marked by ongoing protests against the massive investment in construction of these facilities on land acquired in the name of ‘urban regeneration’, using money which many local people would be better spent on housing, healthcare and education in the existing city. Of particular interest was a small but vocal ‘favela’ community, Vila Autodromo, located on the site for the proposed 2016 Olympic Park on the north shore of Lagoa de Jacarepagua, which protested tirelessly to keep their homes. This conflict prompted the idea of a dual spatial experience of the site, whereby the two urban fabrics, pre- and post-redevelopment could be seen simultaneously: with the user’s naked eye, they would see the new Olympic Park; with a camera, they would see the ghost of the favela.

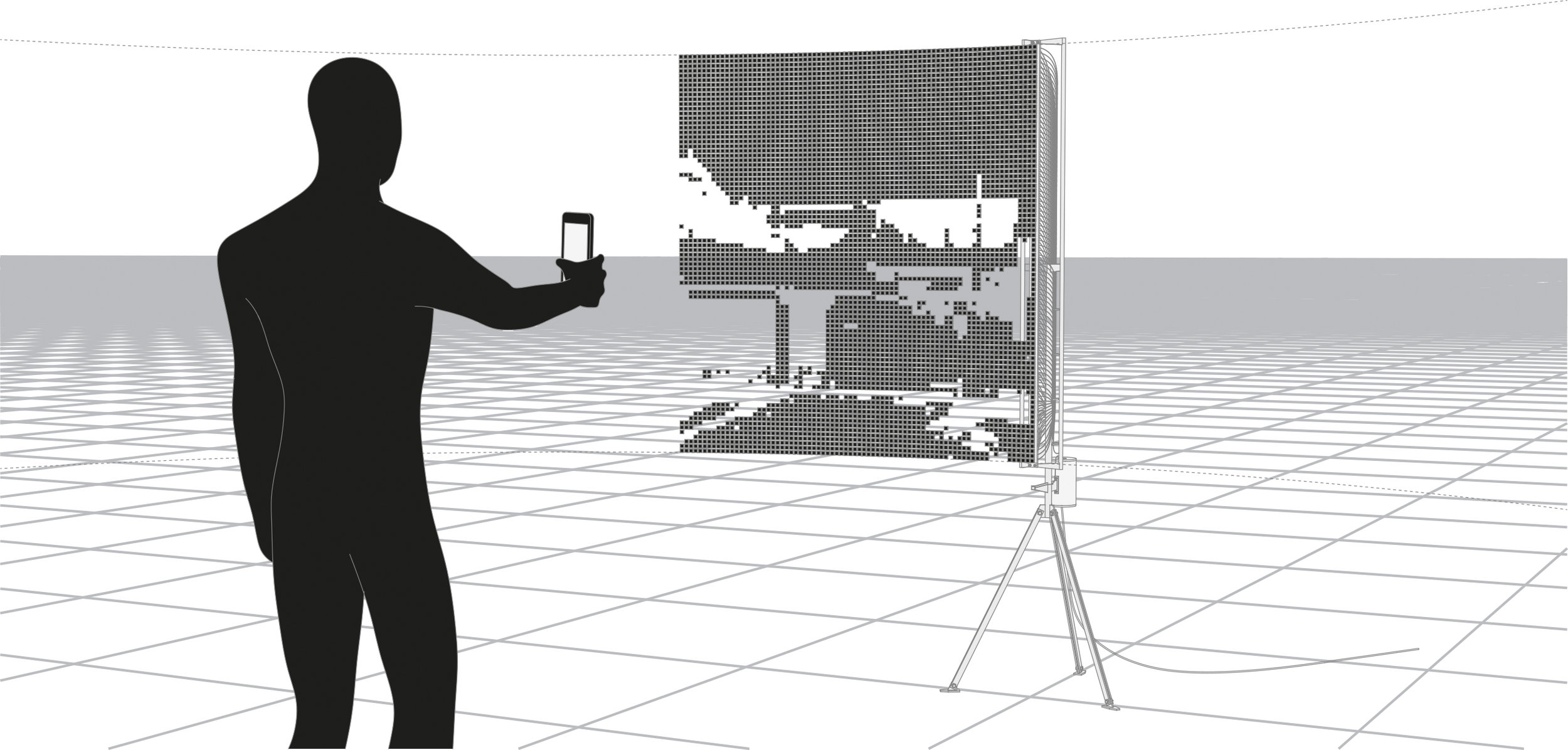

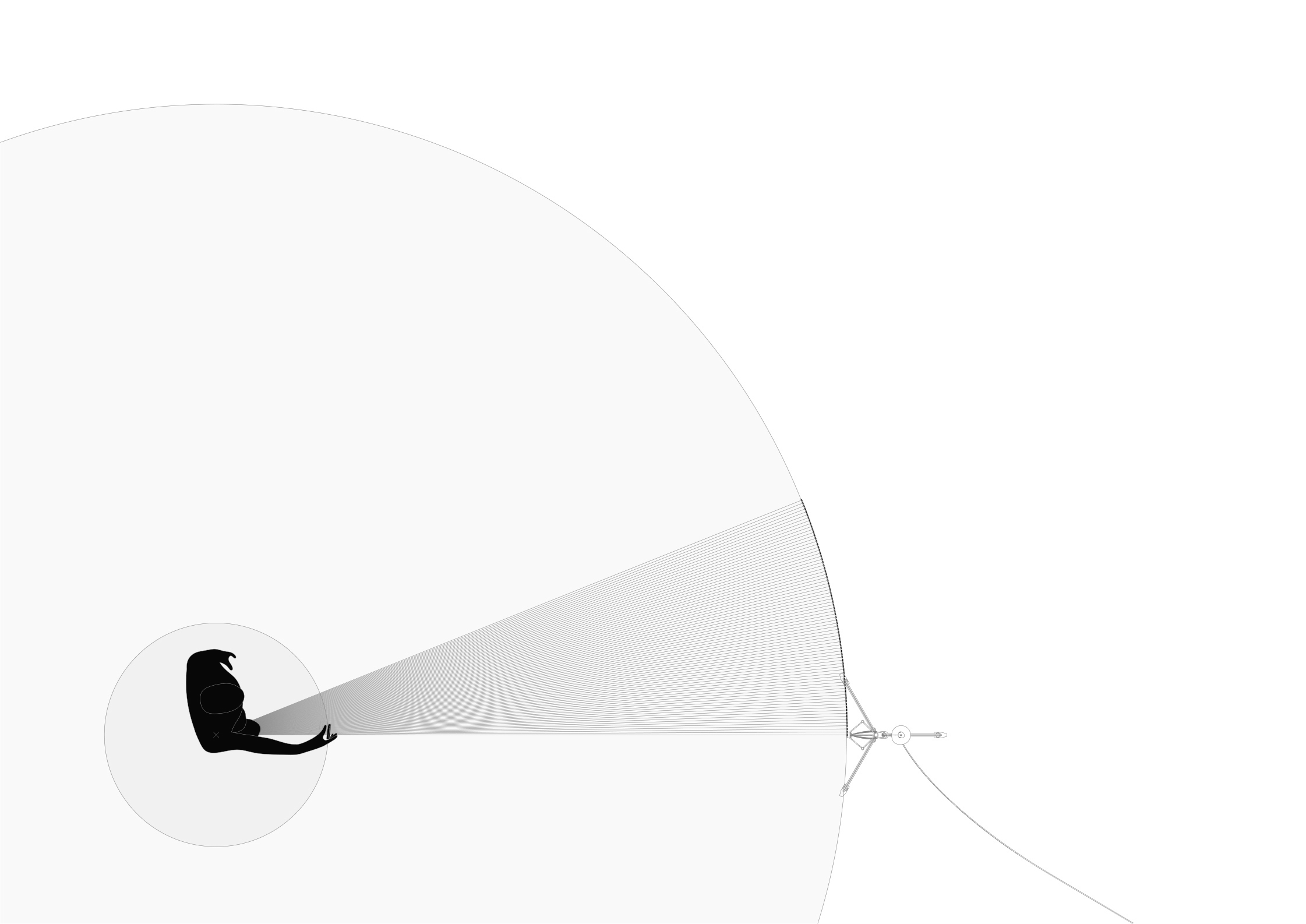

Luckily, despite other advancements in technology, the act of taking a photo – the relationship between the camera operator, sensor, lens, and the scene – remains the same, leaving this process susceptible to interference by optics. Like any other scripted process, it can be hacked: if the light value coming from a point in the original ‘Olympic’ scene is replaced by a light value from a point [with the same spatial relationship to the viewer] in the ‘Ghost’ scene, the camera is fooled, and records the ‘Ghost’ light values as they reach the sensor so the camera records an image of the Ghost Landscape.

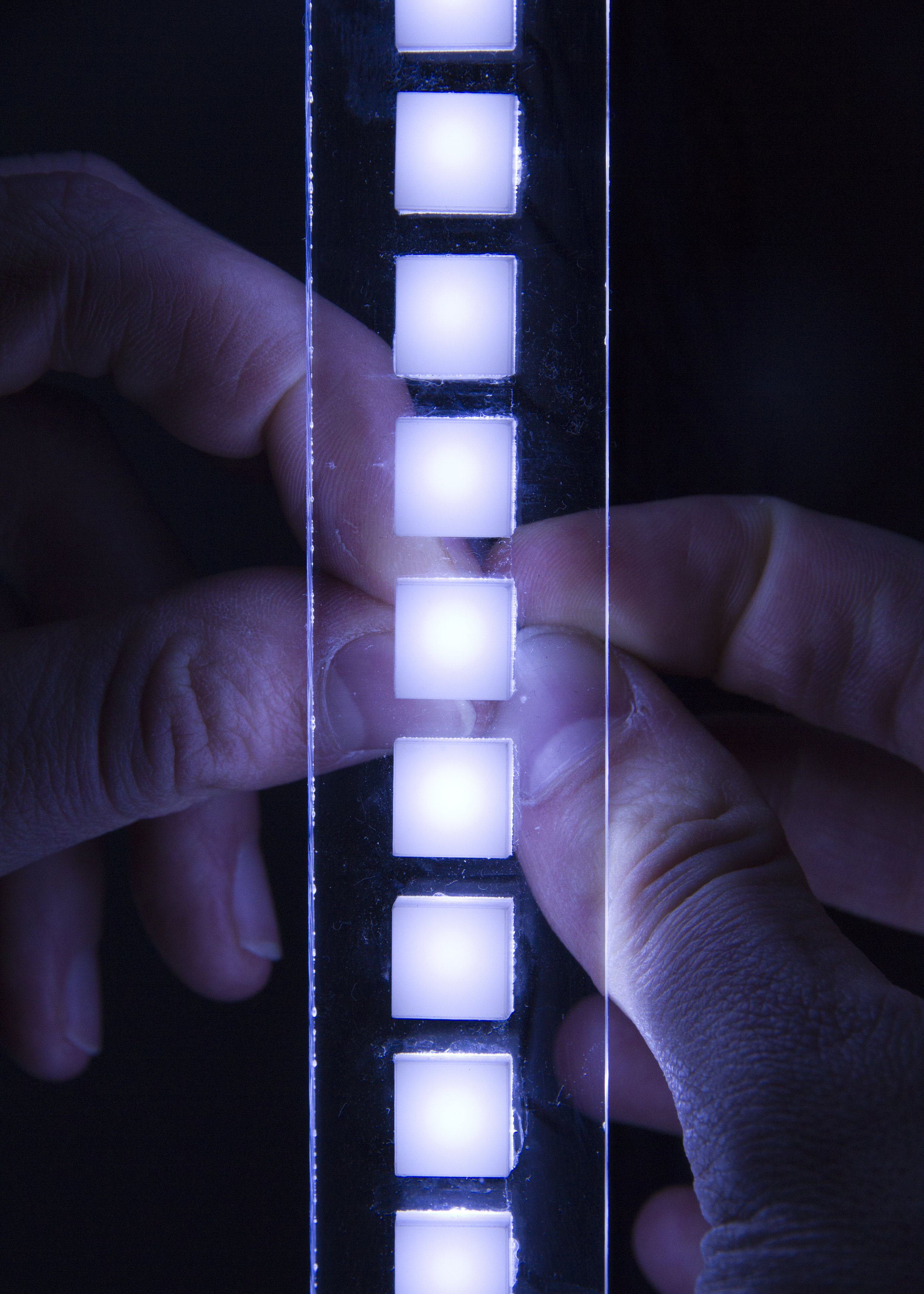

To maintain the subversive aim of the spatial duality, the key driver was the need to be extremely subtle in the way the devices would appear when the ghost landscapes were not specifically trying to be viewed. Influenced by Sao Paulo’s ‘Clean City’ Law introduced in 2006 where each advertisement could only occupy a certain small proportion of the building façade it was on, the size of the ghost landscape image was cropped to a single vertical strip. Positioned on a rig in front of a camera, this strip moved across the photographic field, depicting each corresponding vertical slice of the ghost image as it went. When captured in a long exposure, the whole ghost image was made visible.

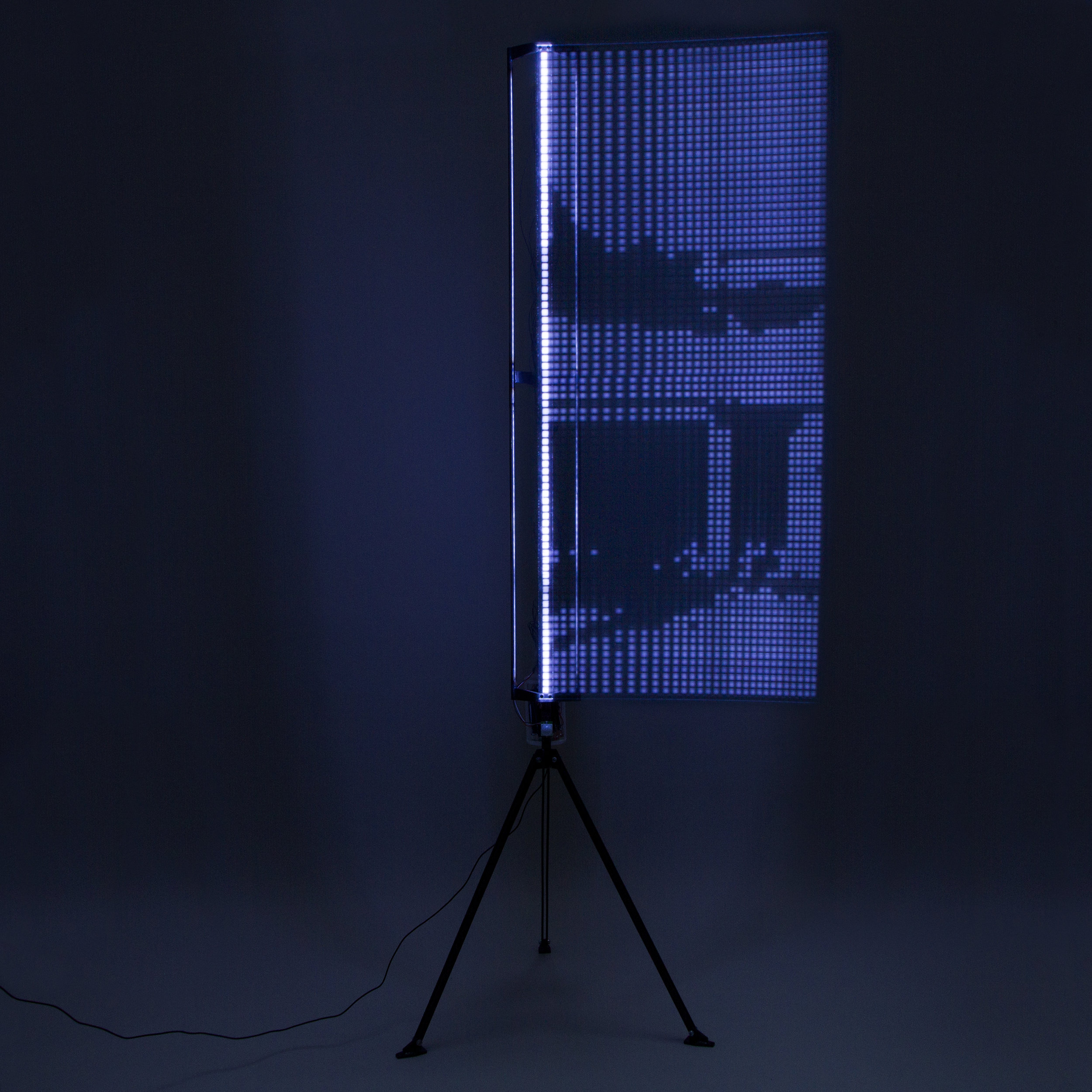

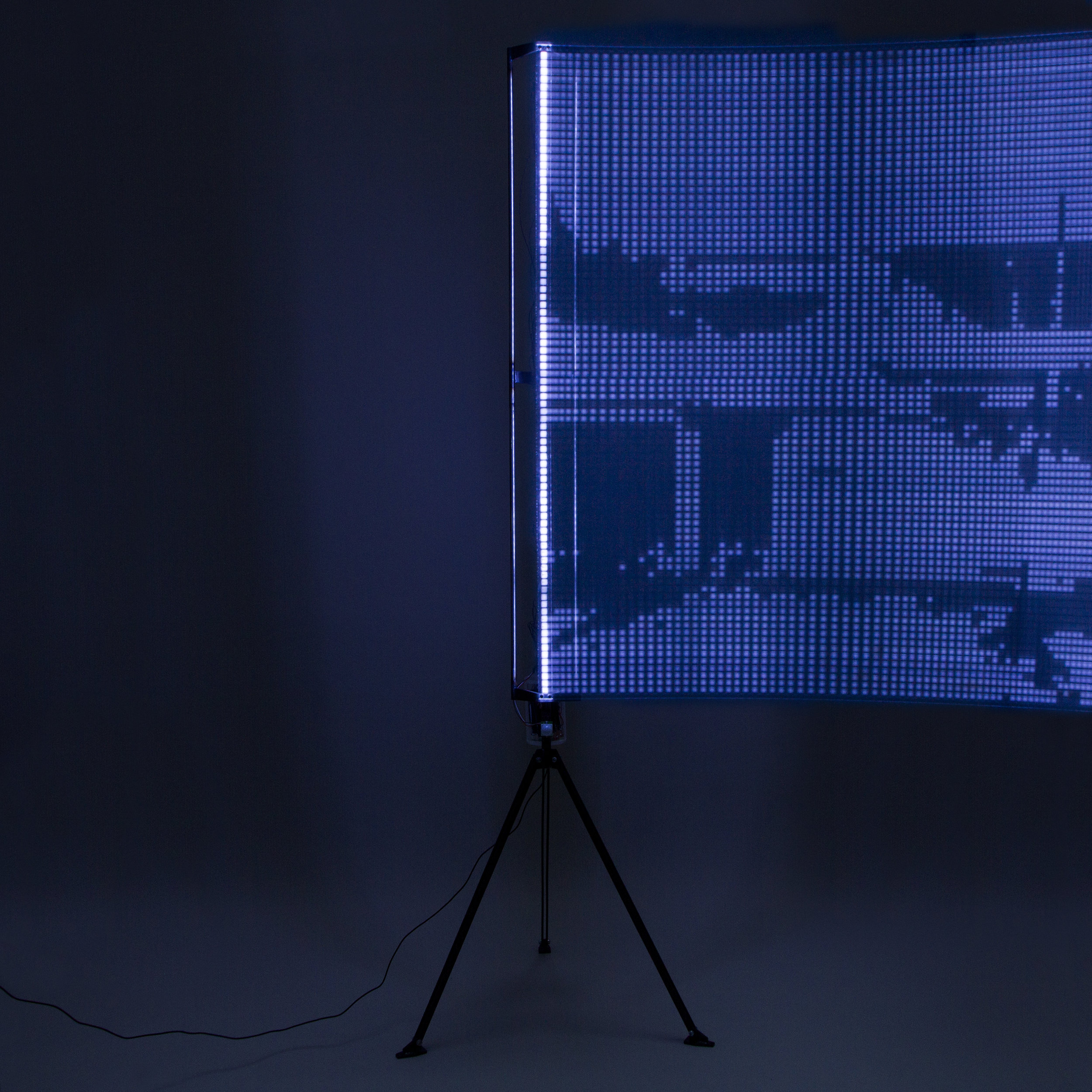

As a spatial proposal so reliant on an experimental application of technology, the two built devices are not designs for the installation itself but demonstrative tools to simulate the specific conditions which the installation would create in reality: the first device simulates one geo-location, the six strips of LEDs which surround the central camera are programmed with a complete digitally sampled panorama of a demolished Favela. The camera’s rotation is controlled with a servo, allowing the image played back through the LEDs to be synchronized to the angle the camera has turned in each time interval. The second device simulates a single LED strip at a 1:1 scale, programmed with a black and white sampled façade from the same Favela, testing the devices within an urban context [Tottenham Court Road], and with members of the public.

If the installation was enacted fully, the hardware would be higher spec (high resolution and full colour), and compacted into a discrete street ornament. Instead, the two devices themselves, designed as demonstrative prototypes, happily show their inner workings. In targeting a specific ‘scripted’ architectural interaction – the act of taking a photograph, Ghost Landscapes questions the role technology could or should play as mediator in the built environment.